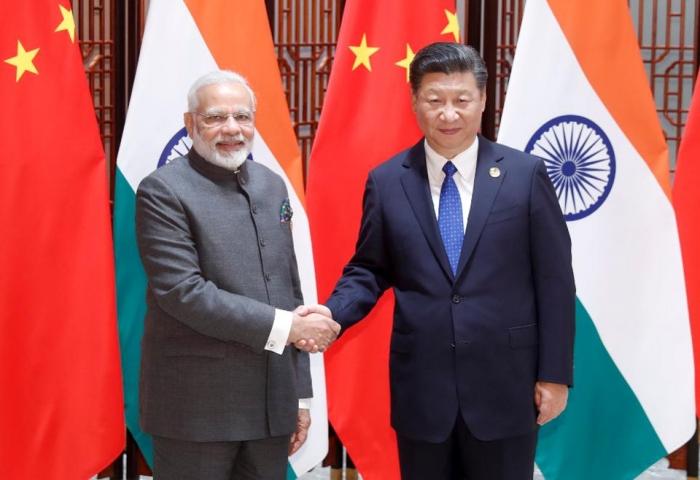

India’s relations with China have oscillated between paranoia and deep suspicion and a calmer assessment of the situation. Last August, when the two countries faced their worst border crisis in four decades over Doklam, the Chinese government publicly reminded India of the lessons of the 1962 war. But the nature of India-China relations is such – and its unpredictable ups and downs – that last week Prime Minister Narendra Modi held an unprecedented “informal” meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, without attendance or agenda, in the Chinese country. Wuhan city.

Also in Forbes: When Modi and Xi meet in Wuhan, investment will most likely drive the agenda

It is attractive to note that despite bilateral and geopolitical differences, economic ties have continued to expand over the years between the two countries. China is one of India’s fastest growing foreign direct investment resources. “In 2017, China invested around $2 billion, up from $700 million in 2016, tripling investment in a single year,” said Mohammed Saqib, secretary general of the India-China Economic and Cultural Council (ICEC). Mauritius was the largest source of foreign investment in India, followed by the United States and the United Kingdom in 2016-2017.

China is also India’s largest trading partner, and India is the largest allocation market for Chinese corporations in South Asia. “Despite being caught in an antagonistic relationship over Doklam, the bilateral industry between India and China reached 84. 44 billion USD in 2017, an increase of 18. 63%, well above the 71. 18 billion USD recorded in 2016. This is a fundamental milestone for both countries,” says Saqib.

Major players teaming up

This year, the bilateral industry in the first quarter reached 22. 1 billion U. S. dollars, a year-on-year increase of 15. 4%. In April, the two countries signed more than 100 industrial agreements worth $2. 38 billion, during the stopover of the Chinese industrial delegation in India.

“As two major emerging countries and major emerging market economies, China and India have a huge domestic market,” Ministry of Commerce spokesperson Gao Feng told Xinhua last week. “The economies of the two countries are very complementary, creating enormous cooperation. “

There is apparently a common confidence in both countries that a hostile stance harms their interests, and stabilizing relations at a time of global uncertainty will pay economic dividends. India’s competitive merit in data technology, software and medicines, as well as China’s strengths in manufacturing and infrastructure development, make both sides herbal partners.

“Of late, China and India are trying to redefine their bilateral relations and their industrial ties are expected to contribute to this,” Saqib said. “In the Asian neighborhood, India is the only country that has the market and strength to absorb China’s excess capacity and investment. India’s GDP, at just about $2. 5 trillion, is equivalent to that of all the rapidly developing ASEAN countries combined.

What does this bring to China?

China’s economy is five times larger than India’s. In recent years, as domestic expansion slowed, China produced more steel, cement and machinery than the country needed. And while it is up to emerging Asia to keep its economic engine running, Chinese corporations have been courted across India to fill its infrastructure gap. Last year, Chinese company Sany Heavy Industry planned a $9. 8 billion investment in India, while Pacific Construction, China Fortune Land Development and Dalian Wanda planned investments of more than $5 billion each.

In 2014, President Xi Jinping, who is exporting China’s state-led style of progress with the aim of creating deep economic ties, promised to spend $20 billion on India’s trade and infrastructure projects over five years. Earlier this year, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a China-led multilateral investment bank, approved financing for projects of around $1 billion in India.

“However, while many MoUs (memorandums of understanding) have been signed through Indian government agencies and Chinese investors, they have not yet resulted in massive infrastructure investments,” Saqib says, noting that Chinese corporations are well-positioned to invest in the sector. cash because they have the capital and technical expertise.

Related: How India Got Wrapped Up In China’s Belt And Road Initiative, Despite Opposing It

Indian startups make a profit

Meanwhile, Chinese investors have poured money into sectors that fall outside the purview of government agencies. “In the last three years, according to data, Chinese and ethnic Chinese investors have invested around $3. 7 billion in Indian startups,” says Saqib. “For India’s startup sector facing an investment crisis, such investments are an incentive for new entrepreneurs. “

In 2015, Alibaba invested $500 million in Snapdeal and $700 million in Paytm. The following year, Tencent invested $150 million in Hike, a messaging app, and a consortium of Chinese investors paid $900 for media. net. In 2017, Alibaba and Tencent announced or closed deals worth about $2 billion: Alibaba’s second tranche of $177 million in Paytm, $150 million in Zomato, $100 million in FirstCry and $200 million in Big Basket. Tencent’s investments included $400 million in Ola. 700 million dollars in Flipkart and a second investment circular in Practo. Last year, even Chinese pharmaceutical giant Fosun Pharma spent $1. 09 billion to gain a 74% stake in India’s Gland Pharma.

“Apart from the virtual area and startups, China’s investments have historically been concentrated in the automotive industry and have been concentrated in the state of Gujarat, home state of Prime Minister Modi, among others,” Saqib said, adding that there has been “exuberance” in India this period. Chinese micro-capital and increased investments in sectors such as prescription drugs and solar energy. “Given the good fortune of recent investments, China could very soon become one of the top 10 most sensible foreign investors in India,” he says.

The Chinese generation discovers a foreign market

Chinese smartphone manufacturers Xiaomi, Huawei and Oppo, all of which have production plants in India, have also enjoyed wonderful good luck in the Indian market. Xiaomi’s sales in India increased by 259% in 2017. The relatively low prices of hard work make India attractive to Chinese investors, offering an ideal hunting ground for the production sector. According to a report by China Briefing, an average Indian employee can be hired for nearly one-fifth of what it costs to employ a Chinese workforce.

More on Forbes: Huawei Is Finally Making A Significant Dent In The Indian Smartphone Market

Tellingly, Chinese companies are showing more confidence in the Indian economy, which is currently growing slightly faster than China and narrowing the gap in competitiveness between the two Asian giants. India ranked 40th compared with China at 27th in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017-18.

Santosh Pai, a partner at Link Legal, a law firm that helps Chinese investors to get a foothold in the Indian market, told CNBC: “Chinese investments have doubled in the last two years. I have no reason to doubt that it will not continue as they have already tasted blood. If you are a Chinese company today with a limitless amount of capital and you look at the whole world and ask, ‘Where is the big bet you can play?’ the answer is India.”

It’s not just China’s capital-hunting, knowledge-sharing, and investments that are game-changers for Indian entrepreneurs. “Even if they get financial advantages from Chinese investments, the long-term gain comes from reading the successes and Chinese corporations in the domestic market,” Saqib explains.

Given that India and China have remarkable similarities in terms of consumption habits and income source levels, there is a “huge learning curve,” he adds. “Chinese investors are helping Indian startups strategically tap into the spaces of market dynamics. As for market control As far as this is concerned, Indian marketers can rely on the Chinese style, and not the American style.