Tommy Kramer’s name continuously pops up in ongoing conversations about the rise of Texas quarterbacks in the NFL.

Texas right now is in a golden era of pro quarterbacks, similar to the formative years of the NFL from 1937-1962 when Sammy Baugh from Sweetwater and Bobby Layne from Highland Park starred in the fledgling league. But Kramer doesn’t fit into that era, either.

Kramer — who passed San Antonio Lee to a state championship in 1971 and earned All-America honors at Rice before a 14-year NFL career — played during an era when Texas was known for producing pro running backs. Players such as Earl Campbell from Tyler, Billy Sims from Hooks, Eric Dickerson from Sealy, Joe Washington of Port Arthur, Roosevelt Leaks of Brenham and Lawrence McCutcheon of Plainview dominated headlines and stat sheets.

Because of the era in which he played, Kramer’s stamp on Texas schoolboy football could easily fade. Inductions into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame in 2009 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 2012 helped remind us of Kramer’s seemingly misplaced feats.

“At the time he played, football in Texas was all about running the wishbone and the veer,” said longtime San Antonio sportswriter Tom Orsborn. “Lee had a head coach at the time named John Ferrera, and he was ahead of his time with throwing the ball. Tommy Kramer’s skill set fit what Ferrera wanted to do.

“They were doing stuff that was unheard of at that time.”

Ferrera was an unlikely pioneer for the passing game. His reputation was as a tough, old-school coach whose smash-mouth practices were legendary. But when it came to offense, he schemed around his talent — the passing arm of Kramer and the athleticism of receivers Richard Osborne and Pat Rockett. Osborne was a future NFL player and Rockett a future Major League Baseball player.

More: Here’s why Texas is the quarterback capital of the NFL

Kramer, who lives in San Antonio but is spending much of this season back in Minnesota, prefers to remember the grassroots of his life in football.

“It started in the seventh grade in the backyard with my dad (a former coach). He hung up a bicycle tire and made me throw passes through that tire four or five days a week,” Kramer said.

“I’d say to myself, ‘If I make this throw, we win the district championship.’ Then when we got into those games in high school, I felt no pressure because I’d already done it right there in my backyard.”

Kramer began the 1971 season playing safety. He became the starting quarterback during halftime of a water-logged season opener against Alamo Heights. He threw the game-tying touchdown pass and kicked the game-winning extra point.

“I only threw for 115 yards or so that night,” Kramer said. “But it was in the rain, we won and I didn’t turn the ball over. A reporter wrote that I was deceptively slow.”

Lee started 18 juniors in 1971, including Kramer. But by season’s end, the Volunteers were the Class 4A (present-day 6A) state champions with a 14-0-1 record, and Kramer was a San Antonio legend.

Kramer led Lee to tight playoff wins over Austin Reagan 19-14, Houston Milby 19-16 and Wichita Falls High 28-27 in the state championship game — the first high school game played in Texas Stadium, the new home of the Dallas Cowboys in 1971.

Trailing Wichita Falls 27-21 with 2:55 to play, Kramer completed passes of 35 and 29 yards to Osborne to tie the score at 27. Then as he had in the season opener, Kramer kicked the winning extra point.

“It seemed like we always came back and won,” Kramer said. “That season was when I got the nickname ‘Two Minute Tommy.’ That name stuck with me all the way through the NFL.”

Kramer set single-season state records with 2,588 yards and 28 touchdowns in 1971. Osborne set state records with 86 receptions for 1,429 yards. Those statistics seem common today, but in 1971 when most teams ran the ball, they got 20-30 fewer offensive snaps than with today’s fast-paced spread schemes.

Kramer downplayed any comparisons to today’s shotgun slinging quarterbacks that pass 40-50 times a game.

“We didn’t set out to throw on every down,” Kramer said. “We got behind in some of our games, and we had to throw. But we were close to 50/50 between the run and the pass. We weren’t just dropping back and slinging it. We ran a lot of bootlegs, sprint-outs and play-action passes.

“Osborn was 6-foot-4 and nobody could cover him. Rockett later ran a 4.32 in the 40.”

As a senior in 1972, Kramer led Lee back to the state semifinals before experiencing his first loss as the starting quarterback — 21-20 to Baytown Sterling. Lee scored late and almost came from behind again, but a two-point conversion attempt failed.

Kramer finished his high school career with a 26-1-1 record, 5,489 yards and 54 TDs passing, and a completion percentage of 62.

He made his college choice because Rice used a pro-style offense. Kramer set Rice passing records from 1973-76 that stood for 30 years. He earned All-America honors in 1976, when he led the nation in passing. Kramer and John Elway of Stanford are the only quarterbacks since 1970 to be named consensus All-Americans while playing for a team with a losing record.

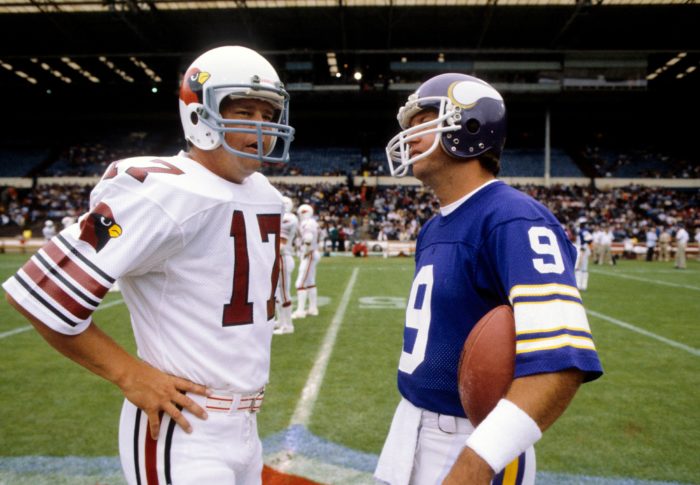

The Minnesota Vikings drafted Kramer in the first round in 1977, and he learned for two years under hall of fame quarterback Fran Tarkenton. Kramer then started for the Vikings for 11 years when he wasn’t injured. He was the first NFL quarterback to pass for 450 yards in a game twice, and he once threw for six touchdowns against Green Bay. He also kept his knack for pulling out last-minute comebacks.

Kramer estimates he suffered 20 concussions during his 14 years in the NFL. He played during an era when NFL guidelines favored defenses — a radical change from today’s rules designed to help offenses score more points and entertain crowds and TV viewers.

“Cornerbacks could literally maul receivers trying to come off the line of scrimmage,” the 64-year-old Kramer said of his playing days. “Now, they have rules to protect the players and allow them to put on a show. I’m fine with that.”

Mike Lee writes about high school football during the season for the USA Today Texas Network newspapers. Have a story idea? Contact him at [email protected].